Barriers to equitable river access persist, but they’re not always what you expect.

Pictured: RiverFest at Bartram's Garden.

With the official start of summer, on-water recreation season has arrived. Here in the region, if you’ve walked the newly renovated trail along Delaware Avenue, cast a line from the Schuylkill Banks, pedaled in Cooper River Park, or paddled on a guided kayak trip, you know first-hand the urban oasis that exists on and along the region’s waterways.

These experiences are possible because of the transformation resulting from 50 years of the Clean Water Act and a massive mobilization in response to its clarion call for “fishable, swimmable waterways.” Take the Delaware River, for instance. Its clean-up from a veritable cesspool and ecological dead zone in the not-so-distant past is remarkable progress worth celebrating. But even so, more is required to make “fishable, swimmable” experiences accessible for everyone. We need to fortify the efforts of the Clean Water Act to battle persistent pollution. We must also address significant barriers to access while fostering a shared-use mentality among those who work and recreate on these waterways.

Removing Barriers to Access

For a community surrounded by rivers, it can be surprisingly difficult to find a safe and comfortable place to get wet! While the Delaware River has made a remarkable recovery from the legacy of industrial pollution, that legacy unfortunately remains in remnants like barbed-wire fences and abandoned and even contaminated properties that too often cut neighborhoods off from the water. Physical access is limited, and where there is access, safety considerations are paramount. It’s important to note that the incidence of drowning is low, but when these horrible tragedies occur, an immediate reaction often comes in the form of more fenced-off areas that not only serve to discourage swimming, but limit the ability of people to get close to their rivers. While it is currently illegal to swim in Philadelphia’s waterways, we should work toward a day when it is safe and legal. Instead of diminishing access further, we believe it’s important to introduce more positive interventions like swimming lessons, on-water safety instruction at the community level, and guided programs. The city's current struggle to hire enough lifeguards to open public pools is just one more manifestation of barriers to access – we need lifeguards to ensure pools and public swimming areas are safe. While persistent barriers to access exist, the Clean Water Act provides the means to ensure that poor water quality is not among them.

The story of water quality gains under the Clean Water Act plays out across many of the most heavily urbanized waterways in our region. One remarkable example is Devil’s Pool in the Wissahickon Creek, where recreational use has been actively discouraged. There are ongoing and persistent structural barriers to safe and equitable swimming access at Devil’s Pool, including inadequate facilities for hygiene and comfort – but, we can celebrate that water quality impairment is no longer the decisive barrier. Sophisticated water quality sampling and pathogen analysis led by researchers at Temple has found that water quality conditions at Devil’s Pool and nearby areas along the Wissahickon comply with the EPA guidelines for safe swimming. From the Wissahickon Creek, to the upper Schuylkill River and the center channel of the Delaware main-stem, emerging data tell a story of steady improvement, including regularly achieving water quality standards for “swimmable” waterways.

Wading In

So the rivers are cleaner … where can we get in? Here in the region, organizations like Bartram’s Garden, UrbanPromise, Independence Seaport Museum, and Glen Foerd are introducing children, teens, and adults, including many in urban neighborhoods, to activities like boat building, kayaking, and even water quality sampling. Investments, including support from the William Penn Foundation, for these initiatives and for destinations like Pyne Poynt Park in Camden and the planned South Wetlands Park in South Philadelphia provide places where people can literally wade in, paddle, and explore the richness of nature. Overall, on- and near-water recreation is up, boat trips are oversubscribed, demand is surging …

Sharing the Waterways

… and the idea of a potential conflict between recreational and commercial use on our rivers is brewing. In a Philadelphia Inquirer article in March, the headline asked “Can big ships and little kayaks both use the Delaware in Philly?” bringing to light the decades-long battle to get a 27-mile stretch of the river in Philadelphia designated for “primary contact” like nearly every other segment of the river both north and south of the city.

As the article explains, some cite safety concerns for recreators from pollution and commercial traffic. However, there is ample evidence that water quality is improving, and there is little to justify the alarm bells regarding commercial traffic. According to National Marine Boating Statistics compiled by the US Coast Guard, across the entire country, of the 299 kayak, canoe, or paddleboard-related incidents in 2020, the number that involved conflict with a commercial vessel? Zero. Of the 260 incidents in 2019? Zero. Tragedies from decades past may be burned into our collective memory, but when faced with the evidence just shared, we must ask if they justify continuing to deny communities access to these magical experiences. For example, this might include a blanket prohibition of on-water educational field trips for district schools, while hundreds of private and charter students safely partake every year.

In the same way that “Share the Road” campaigns have gained traction for cyclists, we need to find a way to convene inclusive conversations that help us “Share the Waterways.” Just look to the controversy centered on Washington Avenue and its new “traffic diet.” That tumultuous experience underscores the importance of listening to communities to shape a vision of shared use that everyone can live with. When it comes to our urban waterways, community-based NGOs and district councilmembers like Jamie Gauthier, Cherelle Parker, and Mark Squilla are playing leading roles in keeping their constituents’ needs front and center while bringing this new vision to life.

Pictured: UrbanPromise's Urban Trekkers program based in Camden, N.J.

Destinations for All

The more pernicious barriers to our waterfronts and riverways – whether physical ones like barbed-wire fences, or constituencies that prevent others from engaging – are all the more challenging for their insidious ties to racial and social injustice. The tension between closing off access to urban waterways vs. investing time, energy, and resources in swimming and water safety education in Black and brown communities, particularly, is not new. The POOL! exhibit at Fairmount Water Works speaks to the unjust, racist gap that exists for in- and on-water proficiency, a gap that has persisted for generations.

Just as not every community has experienced the same levels of historic pollution and neglect, not every community is realizing equal benefit from the rivers’ comeback. Recreation represents an important aspect of community benefit. Just ask city kids about their first paddling experience on the river; you’re likely to hear how the new view of their neighborhood and city from a kayak changed their whole perspective. Our city – and our world – need more fresh perspectives and community benefits like that. It’s time to move the call of the Clean Water Act forward – “yes” to water quality preservation and restoration, and “yes” to equitably sharing the waterways so all can access them.

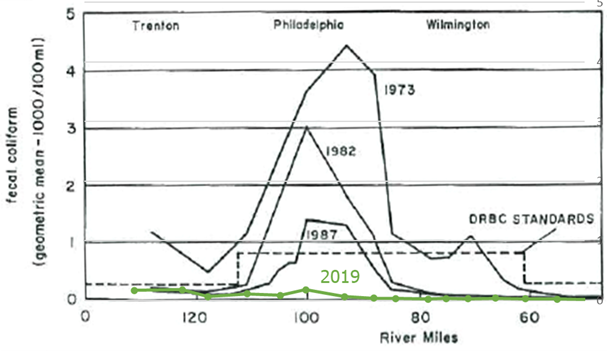

CLEAN WATER ACT REDUCES HISTORIC POLLUTION

Figure 1: Showing progress made in the decades following passage of the Clean Water Act in 1972, the figure above overlays a 2019 snapshot of fecal coliform (pollution) data from the Delaware River Basin Commission boat run atop a plot from a 1988 DRBC paper by Richard C. Albert. The chart shows the decrease in annual mean pollution levels in the 1973-1987 period (Note: the 1988 depiction of “DRBC STANDARDS” is no longer current).